New works by Claudia Hausfeld, Sindri Leifsson, Eva Ísleifsdóttir and Elísabet Brynhildardóttir explore objecthood in a multitude of ways. For the past year, the artists have been engaged in conversation in each others studios and in August 2017 participated in an exhibition in Bjarki’s project space, ca. 1715, run out of a Late-Baroque cabinet in his home. There they presented sketches and preparations for the exhibition, opening their process to an audience while mid way through making new bodies of work. The title of the exhibition points in different directions; in the Icelandic “Munur” refers to things, artifacts hinting to or demanding preservation yet simultaneously the word can signify difference, a comparison of variables while “The thing is” is the beginning of a conversation, explination and a statement on the way of things, objects or conditions.

The current interest in objecthood today must in part stem from the current and unprecendented levels of consumption, production and circulation of goods and the fact that after the industrial revolution, humans for the first time managed to produce objects that supercede time and space. This is the collision of the human and geological time scales, which until recently had not intercepted. Something which takes moments to ignite may take dozens of thousands of years to vanish, indicating our value systems and cultural condition.

In the work of these artists we see different approaches to objecthood. Popplar, a often disputed garden tree which bothers many home owners with its fast growth and invasive roots has been placed in a category with negatively associated plants. In one of Sindri Leifsson’s recent projects, he’s used bits of walnut to tie the breaking wood, stopping it from further cracking in the process of drying. In this manner, Sindri’s work often comments on materiality, displacement and combinations of materials whose properties work against each other. Concerned with construction and the process of change, for this exhibition he has explored the near environment of Skaftfell working directly with objects found on walks through the town and its peripheries.

Eva Ísleifsdóttir’s practice employes humour in an occilation between hope and dispair, addressing important questions into how value is placed and produced. In the exhibition she shows a series of new works, one of which originates in a decades old drawing found inside a book in a fleamarket. In it an imagined traditional Icelandic turf farm is depicted, the cut out shape´s three windows have red nylon curtains glued on the back of the paper. The idea of home and how we remember what we remember, and forget that which we forget appears here as a bitter sweet relic of the contested building form of the turf house, built up over centuries of development, erased from the environment in a matter of decades in the twentieth century. The turf farm still roams around as a foggy memory in our minds, appearing here as a picture of how our imagination of the past becomes a work of fiction through time.

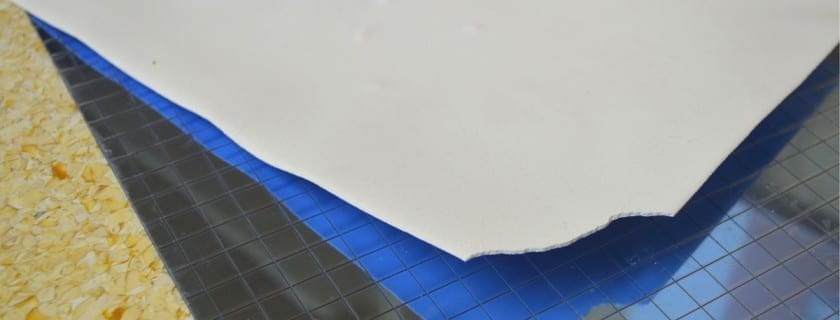

Elísabet Brynhildardóttir has in her latest works explored the material properties of things, their limits and what happens when you turn their purpose upside down. Elísabet has in her drawings reconstructed mistakes from a computer simulation program, which she observed on online forums for amature draftsmen. A rendering of a veil moving in the wind gone wrong kept clading ever more pixels until its complete destruction. In detailed drawing of these mistakes, Elísabet translates them to another material and dimension, revealing the tension between the physical and digital environment. In another work, a graphite drawing lets in the faint winter light over the silver-black surface. On a low standing pedestal, a peculiar bundle of red construction plastic bears a red velvet texture, precariously placed on a red grid. Like dust, temporarily set in its place, the red color is the result of an emergency flare set off inside a small and closed environment constructed by Elísabet, obtaining the poisenous material used to signal emergency, here it is result of an intensional loss of control of the nature of the material.

Claudia Hausfeld employes and comments on photography in her work, where questions of reality appear, and historical narratives are placed evenly along side imaginaries. In her latest work she’s dealt with deformations of documentation of historical artifacts, reconstructing them in a poetic manner to produce bent and broken figures. A photograph of a photograph has been enlarged multiple times and printed on A4 pages and glued together, showing a building from an apparently far away location, reminding of the methods we use to survey the past, and how those methods have changed over time. In photographs printed on paper and ceramics, Claudia has broken up a peculiar looking teapot and rearranged it. The painted pattern reminds of veins in wood. In one of the pictures she has removed the teapot from the surface and patched the image up in a computer software, sampling spots from the image and reconstructing the background to fill the void left over. In that manner, as in many other works in this exhibition, we are reminded that repairs often underline what is missing, and the emptiness becomes tangible.

Curator Bjarki Bragason.

Claudia Hausfeld (b. 1980) works primarily with the deconstruction of the photographic image, creating spaces that play with the reliability of the visual. Questions about the representation of what is visible are translated into objects and text works, combining sculpture, images and sound. Claudia was born in Berlin and lived in Switzerland and Denmark before moving to Iceland in 2010. She studied photography at the Zürich University of the Arts and received a BA from the Icelandic Art Academy in 2012. Hausfeld currently lives and works in Reykjavik, where she co-manages the photography workshop at the Iceland Art Academy and serves as a member of the board of Nýló, the Living Art Museum.

Elísabet Brynhildardóttir lives and works in Reykjavík, Iceland. She graduated from University College for the Creative Arts, UK, in 2007. Ever since her graduation she has participated in various exhibitions and projects. Her works have been shown in Akureyri Art Museum, The Factory in Hjalteyri, The Living Art Museum and Reykjavík Art Museum. In her works Elísabet explores the boundaries of drawing whilst contemplating ideas of impermanence, security and time.

Eva Ísleifsdóttir (b. 1982) lives and works in Athens. She completed an MFA from the sculpture department of the Edinburgh College of Art in Scotland in 2010 and a BA in fine arts from the Iceland Academy of the Arts in 2008. In her latest exhibition, Eva addressed the identity of the artist and the art work, focusing on a critique of society through every day events. Her practice is concerned with hand craft, where the possibly bad copy is more closely related to props than objects of sculptural integrity.

Sindri Leifsson (b. 1988 Reykjavík) graduated with an MFA degree from Malmö Art Academy in 2013 after finishing a BA degree in Fine Art at the Iceland Academy of the Arts in 2011. Symbols and the treatment of materials are repeated themes in Sindri’s works as well as surroundings and elements in the society. His last exhibition stretched itself out of the exhibition space where ambiguous sculptures manifested themselves in Kópavogur Art Museum’s surroundings, shifting the focus towards city planning and spatial behaviour.